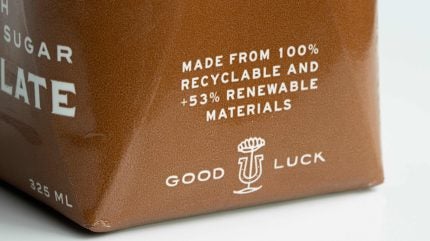

A package marked “100% recyclable” looks like a clear environmental win. For many businesses, that label has become a shorthand for responsibility, compliance, and progress.

Yet recyclability claims often promise more than they deliver. The gap between what is recyclable in theory and what is recycled in practice is wide, and it continues to shape waste outcomes across global supply chains.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Interest in terms such as recyclability claims, recyclable packaging, greenwashing, and sustainable packaging reflects growing scrutiny from regulators, customers, and investors. As expectations rise, businesses are discovering that recyclability alone is an incomplete measure of environmental performance.

Recyclable in theory, not in reality

Recyclability is frequently defined under controlled conditions. A material may be technically recyclable if it can be processed somewhere, under specific circumstances, with the right equipment. Real-world waste systems rarely match those conditions.

Collection infrastructure varies widely by region. Some materials are accepted in one country but rejected in another. Local sorting facilities may lack the technology to separate certain plastics, composites, or coatings, even when these materials carry recyclable labels. When items cannot be sorted efficiently, they are often diverted to landfill or energy recovery.

Contamination compounds the problem. Food residue, mixed materials, and incorrect disposal can render otherwise recyclable packaging unusable. In practice, recyclability rates are shaped less by material potential and more by behaviour, infrastructure, and economics. A claim that ignores these factors risks misleading both businesses and consumers.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataFor organisations reporting on sustainability, this distinction matters. High recyclability on paper does not guarantee high recycling outcomes, yet claims often blur that line.

Market forces and material value

Recycling only works when there is demand for the output. Materials must have sufficient value to justify collection, sorting, and reprocessing. When markets weaken, recyclability claims lose relevance.

Low-grade plastics, coloured materials, and complex packaging formats often struggle to find buyers. Even if they are collected and sorted, they may be stockpiled, exported, or discarded if reprocessing is uneconomic. Shifts in global trade policy and commodity prices can change outcomes quickly, turning a once-viable recycling stream into waste.

This market dependency exposes the limits of static claims. Packaging labelled recyclable today may not be recycled tomorrow if demand collapses or regulations change. Businesses that rely solely on recyclability as a sustainability indicator risk anchoring their strategy to forces beyond their control.

From a supply chain perspective, focusing on material recovery rates and end markets provides a clearer picture than relying on recyclability labels alone.

Recyclability versus environmental impact

Recyclability claims also tend to overshadow broader environmental considerations. A material can be recyclable yet still carry a high environmental footprint due to energy-intensive production, long transport distances, or low recovery rates.

In some cases, prioritising recyclability leads to trade-offs that increase overall impact. Lightweight packaging may improve recyclability but reduce protection, increasing product damage and waste. Multi-material solutions may improve shelf life and reduce food waste but be excluded from recycling systems.

A lifecycle view challenges simple narratives. Environmental impact is shaped by how much material is used, how well it protects the product, how often it is recovered, and what replaces it after use. Recyclability is one variable in that equation, not the outcome itself.

For B2B organisations, this distinction is critical. Sustainability strategies built around a single attribute are vulnerable to criticism and may miss opportunities for more meaningful improvement.

Regulatory and reputational risk

As awareness grows, regulators are tightening rules around environmental claims. Vague or unqualified recyclability statements are increasingly challenged, particularly when they do not reflect real disposal pathways. Claims that are technically accurate but practically misleading can still attract scrutiny.

Reputation is equally at stake. Customers and stakeholders are becoming more informed and more sceptical. When recyclable packaging is discovered in landfill or incineration streams, trust erodes quickly. The risk is not limited to consumer-facing brands; B2B suppliers face pressure from clients seeking credible data for their own reporting.

This environment demands precision. Clear, contextualised communication about what recyclability means, and where it applies, is safer than broad claims designed to reassure at a glance.

Moving beyond recyclability claims

Recognising the limits of recyclability claims does not mean abandoning recycling. It means placing it in context. Effective packaging strategies consider local infrastructure, material recovery rates, contamination risk, and end-market demand.

Reducing material use, improving reuse systems, and designing for durability often deliver more reliable environmental gains. Where recyclability is pursued, aligning materials with established, high-performing recycling streams increases the chance of real recovery.

Measurement matters. Tracking what is actually recycled, rather than what could be recycled, shifts the focus from intention to outcome. This approach supports more honest reporting and more resilient sustainability strategies.

A more credible path forward

The limits of recyclability claims lie in their simplicity. They reduce complex systems to a single label, masking the realities of waste management and material recovery. For businesses operating in complex supply chains, this simplification is no longer sufficient.

Credible sustainability requires asking harder questions: Where will this packaging go? Will it be collected, sorted, and reprocessed here? What happens if markets change? By addressing these questions, organisations move beyond labels towards strategies grounded in real-world performance.

In doing so, recyclability becomes what it should have been all along: one useful tool among many, not a proxy for sustainability itself.